On the evening of March 3, 1991, Rodney King and two passengers were driving west on the Foothill Freeway (I-210) through the Lake View Terrace neighborhood of Los Angeles. The California Highway Patrol (CHP) attempted to initiate a traffic stop. A high-speed pursuit ensued with speeds estimated at up to 115 mph (185 km/h), along freeways and then through residential neighborhoods. When King stopped, CHP Officer Timothy Singer and CHP Officer Melanie Singer (his wife), arrested him and two occupants of the car.

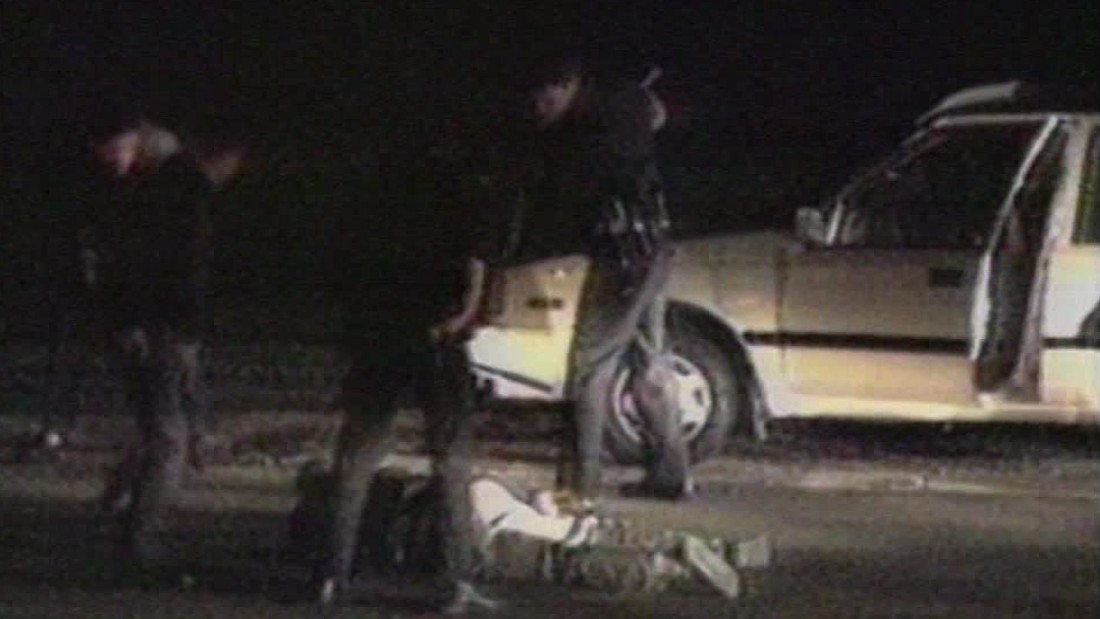

After the two passengers were placed in the patrol car, five white Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) officers – Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Theodore Briseno, and Rolando Solano – surrounded King, who came out of the car last. They tasered him, struck him dozens of times with side-handled batons, and tackled him to the ground before handcuffing him. Sgt. Koon later testified at trial that King resisted arrest, and that he believed King was under the influence of PCP at the time of the arrest, which caused him to be very aggressive and violent toward the officers. Video footage of the arrest showed that King attempted to get up each time he was struck, and that the police made no attempt to cuff him until he lay still. A subsequent test of King for the presence of PCP in his body at the time of the arrest was negative.

Unknown to the police and King, the incident was captured on a camcorder by local civilian George Holliday from his nearby apartment. The tape was roughly 12 minutes long. While the tape was presented during trial, some clips of the incident were not released to the public. In a later interview, King, who was on parole for a robbery conviction and had past convictions for assault, battery and robbery, [said that he had not surrendered earlier because he was driving while intoxicated under the influence of alcohol, which he knew violated the terms of his parole.

The footage of King being beaten by police became an instant focus of media attention and a rallying point for activists in Los Angeles and around the United States. Coverage was extensive during the first two weeks after the incident: the Los Angeles Times published forty-three articles about it, The New York Times published seventeen articles, and the Chicago Tribune published eleven articles. Eight stories appeared on ABC News, including a sixty-minute special on Primetime Live. Upon watching the tape of the beating, LAPD chief of police Daryl Gates said: I stared at the screen in disbelief. I played the one-minute-50-second tape again. Then again and again, until I had viewed it 25 times. And still I could not believe what I was looking at. To see my officers engage in what appeared to be excessive use of force, possibly criminally excessive, to see them beat a man with their batons 56 times, to see a sergeant on the scene who did nothing to seize control, was something I never dreamed I would witness. Before the release of the Rodney King tape, minority community leaders in Los Angeles had repeatedly complained about harassment and excessive use of force by LAPD officers. An independent commission (the Christopher Commission) formed after the release of the tape concluded that a "significant number" of LAPD officers "repetitively use excessive force against the public and persistently ignore the written guidelines of the department regarding force," and that bias related to race, gender, and sexual orientation were regularly contributing factors in use of excessive force. The commission’s report called for the replacement of both Chief Daryl Gates and the civilian Police Commission.

Charges and Trial

The Los Angeles County District Attorney subsequently charged four police officers, including one sergeant, with assault and use of excessive force. Due to the extensive media coverage of the arrest, the trial received a change of venue from Los Angeles County to Simi Valley in

neighboring Ventura County. The jury was composed of nine White people, one bi-racial

male, one Latino, and one Asian American. The prosecutor, Terry White, was black.

On April 29, 1992, the seventh day of jury deliberations, the jury acquitted all four officers of assault and acquitted three of the four of using excessive force. The jury could not agree on a verdict for the fourth officer charged with using excessive force. The verdicts were based in part on the first three seconds of a blurry, 13-second segment of the videotape that, according to journalist Lou Cannon, had not been aired by television news stations in their broadcasts.

The first two seconds of videotape, contrary to the claims made by the accused officers, show King attempting to flee past Laurence Powell. During the next one minute and 19 seconds, King is beaten continuously by the officers. The officers testified that they tried to physically restrain King prior to the starting point of the videotape, but King was able to physically throw them off.

Afterward, the prosecution suggested that the jurors may have acquitted the officers because of

becoming desensitized to the violence of the beating, as the defense played the videotape

repeatedly in slow motion, breaking it down until its emotional impact was lost.

Outside the Simi Valley courthouse where the acquittals were delivered, county sheriff’s deputies

protected Stacey Koon from angry protesters on the way to his car. Movie director John Singleton, who was in the crowd at the courthouse, predicted, “By having this verdict, what these people done,they lit the fuse to a bomb.”